A Debt I Cannot Repay

--by Joel GrowI learned so much at Western Reserve Academy, my high school. Really, I began to become a whole person there. That’s not unusual for a teenager, I know, but Reserve helped guide and form the kind of adult I was to become.

One’s parents, of course, are a big part of that molding of the adult-to-be. But as a teenager I was at that stage of development when it was appropriate and inevitable that I would be looking outside my parents’ fine example and guidance. I was a pretty timid kid, at least in part because of my parents’ over-protectiveness, linked to my having been born with spinal defects resulting in surgeries--and braces on my back and legs--for me, and much anxiety and worry for my folks.

So when I arrived at Reserve, I was ready to grow and change, even though I did not know it, even though I feared it. As a small-town, middle-class boy, I felt more than a little intimidated by the wealth, self-assurance, and talent around me. My own lack of confidence led me to have a bit of a chip on my shoulder about what I thought I didn’t have. At times I felt terribly “outside” and lonely. I was perfect fodder for Reserve.

And how lucky we were to arrive at Reserve when we did! Each of us had our own master or group of masters (are they still called “masters,” I wonder?) who were special for us. From Max LaBorde, Elinor Roundy, and James Gramentine, I learned about research and about thoughtfully and clearly expressing myself on paper. Under Bill Appling’s guidance, I began to love vocal and choral music.

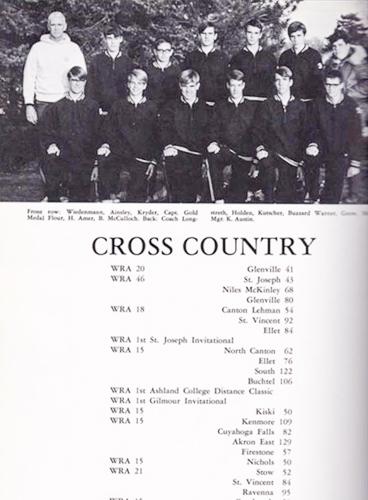

And for all that, Reserve for me was and is about Stretch, Frank Longstreth. I studied Latin with him, worked in the summers for him at his day camp, and ran cross-country and track for him. I didn’t know why it felt so important to do well for Stretch. It just did.

Thus began 44 years that would change the lives of hundreds, no, thousands, of kids. For me, other than my parents and my wonderful wife Rebecca, Stretch is the most important person in my life. And I know I am not alone in that.

I learned a lot about running from Stretch, and studying, too. I learned how when you work hard, things get better, in class or on the track. He worked us till we threw up and cramped, and badgered us till we hated him for it, bless him. I recall after running in the Junior Varsity section of the big multi-team Gilmour Invitational, and having what was for me a very good day, I overheard Stretch tell JV coach Rich Adam that “Grow is today’s hero. He’s really getting the message.” He said it for me to hear, I’m pretty sure, and I still puff up when I recall it now. My late start in athletics meant that I was absolutely dreadful when I began to run. But if I improved to merely terrible, Stretch crowed about me the same way he did over the captain of the team. Similarly, if I loafed in practice or a meet, not giving my very best, he’d ream me out in 1st-class Marine language that would curl your toenails. In the classroom he was the same way: the ever-present needle, balanced (well, sort of) with the occasional encouraging word. He loved to win. But what he loved more was teaching kids to do more than they ever dreamed they could. With that approach, he won every track meet in his first eight years at Reserve, and during my 4 years, our cross-country team went 179-1. This was all at a tiny school of 200 boys spread over grades 9-12.

Stretch was also pretty playful. He was so much a part of Kepner’s pub that he had a booth with his name on a brass plaque. If you were in that booth and Stretch walked in, you had to vacate. He went on a famous late-night swim in the town water tower. He “streaked” the American Legion Hall. His pals were to take his clothes and he’d run through, going out the back door where his pals would give him back his clothes and he’d get dressed.

Well, the pals locked the back door, so he had to run back through the Hall in the other direction. When he got outside, his pals--and his clothes--were nowhere to be found. He ran from hedge to hedge through backyards all the way home.

In my very last race, in the Interstate Meet—our league championships—Stretch told me, “This is your day, Joel.” Later, in the 440, I was in third place coming out of the final turn. Stretch was standing there and yelled “OK, Grow, just like we planned it. Take these two guys right NOW!”

We of course hadn’t planned anything of the sort – Stretch was just trying to psych them out. But you could see those guys begin to fold up right there. As I closed on them, Stretch’s big voice boomed over the crowd....

“C’mon Joel. C’mon Joel! C’MON, Son. C’MON, Son!" I still get chills and misty eyes when I recall it now. I caught one of those guys and nearly caught the second, running a time that was my best ever by a lot. Stretch was as thrilled as I was. More, maybe.

So I learned from Stretch, as I had from my dad, how to show up every day ready to work. From Stretch I also learned how to grow and achieve and even to begin to excel. But I learned something much more important.

What Stretch taught me is that what makes you a man isn’t what’s in your bank account or your garage or winning the 440 or scoring highest on the SATs. It’s what’s in your jock and what’s beating in your chest. I’ve achieved some things I hoped for and had some big disappointments. But I’ve never quit on something I really wanted to do. What’s important is looking at the easy ways out, at all the good reasons to quit, but still not quitting. It’s losing, failing, and keeping going anyway. It’s striving, with victory not anywhere in sight and in fact quite unlikely, just because the striving itself has become the point, the payoff. I’ve been knocked down plenty of times, but I’ve always gotten back up and gotten back to work. So I’ll never have to look myself in the mirror and ask myself: “Gee, what if you’d tried just a little harder, hung in there a little longer?” I’ll never have to look at a quitter.

That’s what Stretch gave me.