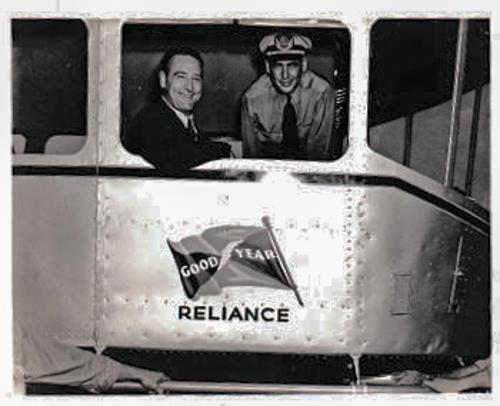

Dad, Lou Gehrig, and the Goodyear Blimp

It was the 4th of July when I was 3 years old, and Uncle Jake and Aunt Dot were over for a holiday cookout with their kids, my cousins Gary and Sandra. Sandy was about 15, I guess, and I thought she was wonderful, and I was sure she must be the most beautiful person on the planet. She smelled good, too.

We were playing wiffle ball, with the white plastic ball and one of those big, fat, red plastic bats. Well, I didn’t know quite what this was all about, but I did know that I liked it when it was my turn to bat, because Sandy leaned down and wrapped her arms around me to help me swing that bat as Uncle Jake gently lobbed the ball to us underhanded. If I even knew the idea was to hit the ball, I didn’t want to, but preferred instead to just keep swinging back and forth in Sandy’s embrace. I can still see in memory how the sun shone on the tiny strawberry blond hairs at her wrist, and how her nails were not long and tapered, but cut almost straight across, no doubt because Aunt Dot thought she was too young for long nails.

Then, when we did finally connect, everyone was yelling “Run, Joel, run, run!!” So I ran…in the wrong direction of course, aimlessly circling as fast as I could. Then—oh, miracle of miracles--Sandy scooped me up in her arms and began to carry me around the makeshift bases—1st base was a clothesline pole, 2nd base was my sandbox, 3rd base was the big silver maple tree, and home plate was, I believe, a literal paper plate held in place by a rock. So there I was, bouncing along in Sandy’s arms, shrieking with laughter and joy as we rounded the bases, with Uncle Jake chasing us, trying not very hard to tag us out. We reached home and everyone yelled, “yea Joel, yea, Joel.” How could I possibly not have fallen in love with baseball right then and there? Later, when it was getting dark, and I was falling asleep on grandma’s quilt spread out on the lawn, loving arms gathered me up and carried me upstairs. I remember the scratch of Dad’s end-of-the-

Most of us have some sort of fond memories about baseball. No, you say? You “never played baseball”? Well, did you ever play wiffle ball at a family gathering like the one I just described? Ever play softball (and steal a kiss behind the dugout) at a church picnic softball game? Ever simply play catch with a ball? Then you’ve played baseball.

When I was a kid, I guess from the time I was in school, when the weather was right for it, I’d wait for Dad when he was coming home from work, so we could play catch. This continued off and on for many years. Dad would get home, and I’d be sitting eagerly on the front steps, or waiting out back in the yard. We’d head out back and he’d take off his suit coat and tie and place them carefully under the big maple tree that had served as 3rd base back when Cousin Sandy carried me around the yard in her arms.

So, we’d start to play catch, throw and catch, throw and catch, slowly moving farther apart as we warmed up. Dad would ask about school or, in the summer, about what I’d been up to that day, or he might talk about something that had happened at his job. After a little while, though, we’d usually get quiet and settle completely into the slow, rocking, back-and-forth rhythm of throw and catch, throw and catch, throw and catch----a steady pendulum beating like our own pulse, the only sound being the slap of ball into glove. That sound became the mantra for our shared meditation, a sweet, still oneness with the ball, the glove, and each other. I felt close to my father in those moments in a way that I never felt any other time. We never, ever talked about it, but I am completely sure that he felt the same way, and that we dared not analyze it or even talk about it for fear of spoiling it. After a while one of us would drop the ball, or Mom would call out the window that dinner would be ready in half an hour, the mood would be gently broken, and we’d start to talk again and finish up playing catch. Dad would go over and sit down under that maple tree, and sometimes he’d ask me to run and get him a beer from inside. When he said to bring a glass, I ran faster, because I knew he was going to pour a little into that glass for me, always with the admonition, “Don’t tell your mother.” Now, most likely, Mom knew that he gave me the occasional sip of beer and thought nothing of it, but that shared secret, that bond between men, made me feel all grown up, and wonderfully close to my Dad.

Sometimes, as we sat under that tree, he’d return to telling me about work, or to asking me about my day, but sometimes he’d tell me some kind of story. I think his favorite was the one I call: Dad, Lou Gehrig, and the Goodyear Blimp.

Except that wasn’t that, after all.

Dad got up early the next morning and walked the 6 miles out to Wingfoot Lake, found that foreman, and, when the foreman asked what Dad was doing there, he said “I’m here to work.” The foreman said “Kid, that was just for one day. I don’t have any more work for you.” Dad said “Sure you do. That floor needs sweeping, those doors could use a coat of paint, and your windows need washing.” The foreman eyed Dad for a long moment, rolling his wet, chewed-up cigar around his mouth, and finally said “OK, kid. There’s the broom.” And thus began 44 years of Dad working for Goodyear.

He swept, cleaned, and painted for a few weeks, and then they needed someone to help with the building of the blimps, so they started Dad on that. In about a year, he got to start flying on the blimps, too, and eventually was on a regular crew. He and Mom were married by then, and they traveled around a good bit with the blimps, to Florida, California and finally in World War II, when the blimps flew up and down the East and West coasts escorting merchant Marine convoys and scouting for enemy submarines, of which they saw plenty. But before that, in the late ‘30s, they were stationed in New Jersey, where they flew from Teterboro Airport out over the NY World’s Fair in Flushing Meadow, Queens. Now, when they went on these flights, they often took along passengers. There were only a few seats in those gondolas, so the passengers had to have some kind of a connection to get on those flights.

For the whole ride over from Jersey, Dad’s pals were riding him, saying it wasn’t going to work. So they made a bet that, if Dad got them in free, they’d pay for all the beer and hotdogs, and if Dad didn’t get them all in for free, he’d have to buy the tickets AND the refreshments. Ouch!

Lou had told Dad a particular ticket booth to go to, and had described the guy who’d be there, with whom Lou had set up the arrangement for his guests. He had horn-rimmed glasses, and always wore the same green and yellow checked tie. When they got there, dad found the booth, and it looked like the right guy. He definitely had the horn-rimmed glasses and, sure enough, wore a tie that had at one time been simply green and yellow checked, but by now had also become the florid resting place of a lifetime of blueberry pie and coffee stains. And so they got in line. As they worked their way up closer to the booth, Dad’s pals were razzing him, saying they were going to eat a LOT of hotdogs, to be paid for by Dad, who was now beginning to get nervous, hoping he had enough cash.

Finally, Dad was next in line. He stepped up to the ticket booth ... and just stood there. The green-and-yellow Tie Guy in the booth was counting money and, without looking up, grunted “yeah?” The moment had arrived. It was time to use Lou Gehrig’s password. Dad cleared his throat and spoke:

“Lou sent me.”

There was a pause. Tie Guy stopped counting and looked up.

“What did you say?”

Uh-oh. Dad felt like he’d made a big mistake and was about to be embarrassed.

Gulp.

“Uh….Lou sent me?”

Tie Guy: “ Buddy, how many are in your party?”

“Six.”

“Friend, you just step over to the side and wait right there.”

With that, Tie Guy snapped down the little shade over the ticket window, flung open the door in the back, and went sprinting into the Stadium. In a couple of minutes he came back, with six ushers. Dad and Mom thought for a second they were going to be thrown out, but Tie Guy graciously asked, would you folks come in with us, please?

Those six ushers escorted the six Ohioans into Yankee Stadium, with Tie Guy clearing the way, telling ticket-takers and other stadium employees: “It’s OK, they’re with Lou.” The crowd parted like the Red Sea. They were led to a private box right behind the Yankee dugout, where the ushers, under Tie Guy’s direction, didn’t simply wipe off the seats. They polished those seats! It was the box of Ed Barrow, the Yankee president in those days. One seat was pointed out as being strictly off-limits. It was Mrs. Barrow’s seat, and they never knew if she’d show up for a game. Dad and his friends tried to tip the ushers and Tie Guy, but they all said. “No thanks, pal. You’re with Lou. It’s my pleasure.”

The vendors appeared with hotdogs, beer, peanuts and all the rest, all without being asked. None would take a dime. “That’s OK, friend. You’re with Lou.”

So there they sat behind the Yankee dugout….and rooted for the Indians. Nearby fans looked on in shock, clearly wondering just who these crazy people were, and even Yankee players—DiMaggio, Ruffing, Dickey, Gomez, and more--poked their heads out from the dugout, and gave them some joshing about it, but it was all friendly and good-natured, if a bit perplexed. Finally, a familiar-looking fellow came climbing over the railing to the box and sat down next to Dad and asked: “Buddy, just who the hell ARE you?” Dad’s interrogator was Slapsy Maxie Rosenbloom, the former Light Heavyweight boxing champion who was just beginning a career as a newspaper columnist and character actor that would include 100 movies and a prominent role in the TV Golden Age drama Requiem for a Heavyweight. In later years he was a frequent guest on the Tonight Show and other talk shows where he would tell his wonderfully funny stories about his boxing years. Maxie, who was quite the raconteur, spent the rest of the game hoisting a few beers with Dad and Mom’s gang, keeping them—and everyone in the stands and dugout who could hear him--in stitches the whole while.

All that packed into one afternoon!

So Dad was a bit of a hero that day to his friends. He felt lucky to have serendipity lead him to meet the great Lou Gehrig, and grateful to have been able to treat his friends to such an extraordinarily special day. This was a young guy, still in his 20s, who grew up in a house without indoor plumbing or electricity, so it’s easy to see why that might have been Dad’s favorite baseball memory, his favorite story. He had come a long way.

Most of us have stories that are special to us, about family, or our hometown, or a special teacher. We all love to pass them on, in the hope that we can let others know what was so special about that family member, or our home town, or that teacher.

So of course I love to tell Dad’s story myself. It’s unique, and wonderful, and it’s about my Dad, whom I miss every day. But it’s not my favorite baseball memory.

My favorite baseball memory is the one about the steady, slow, rocking, back-and forth rhythm of throw-and-catch, throw-and-catch, throw-and-catch---the slap of ball in glove—that sound the mantra of the sweet, still oneness of meditation I shared under the big maple tree in our back yard, a lifetime ago, with my Dad.

--Joel Grow