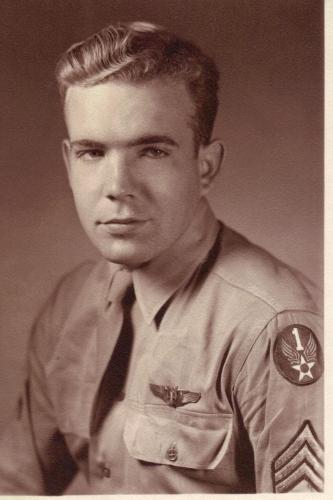

Veteran Bill Claytor

Bill Claytor

Bermuda. Valentine’s night, 1945. Their B-24 had taken off around midnight from an airfield, loaded with generators and other supplies, bound for Sicily. The night was pitch-black with neither sun nor moon to help the crew navigate, and no one saw the German U-Boat surfacing from the waters below, its newly devised deck guns aimed at the sky. Eight men died that night when their plane was shot down into the cold Atlantic waters. Bill Claytor and his buddy George, though, were able to escape the submerged plane by shooting out a window and hanging on to their Mae Wests for dear life. “In that water I had a lot of time to visit God,” he recalls now, but for fifty years Bill was not able to speak about that night.

Bill and George endured the whipping winds and the roiling waves for seven hours, the only survivors of the attack. They were able to secure a Bombay tank to buoy them up over the whitecaps of the angry ocean, but a numbing cold soon set in. “When you stop feeling pain, that’s when you worry,” says Claytor. His eyes sadden in the telling of his story. “That was the best crew I ever served with,” he declares.

William Claytor was born in Loudoun County, Virginia in 1921, the son of two school teachers who tried to make a go of farming but who eventually lost their farm in the Great Depression. He grew up hearing war stories from his Uncle Joe who had fought in the Civil War, so it wasn’t surprising to his family that he enlisted in the Army Air Corps when he turned 18. Bill reported for duty at Langley Field in 1940 where he started out helping on the flight lines before learning to fly observation planes. He quickly made Sergeant and earned his pilot’s license.

His bomb squadron eventually flew to Newfoundland and spent more than a year hunting for German submarines, but it didn’t take long to discover they had two enemies: the Germans and the weather. While the German U-Boats were intercepting all vessels (including merchant ships) heading for England, the furious snow was whipping across the plains where Bill and his buddies spent three weeks sleeping in their bags, burrowed under the snow for warmth, while their barracks were under construction. Their mission was to drop depth charges on German submarines and then watch for the oil slicks or other debris to show the sub had been hit. “It was hard for a country boy to see people die in the ocean,” he recalls.

Bill spent a total of five years serving in the North Atlantic where he eventually worked teaching pilots. “War was a big experience for a boy raised on a farm,” he says. When he was finally discharged, he discovered that his records couldn’t be found. He told the army, “I’m going home.” They said no. “Suppose I go home.”

After returning home, Bill involved himself with his family, his church, and the countless young people whom he has encouraged and mentored over the years. “Serving in the Army Air Corps gave me a lot of knowledge,” Bill says. “I met a lot of good people and I appreciated a lot of people. I also have an appreciation for living. I told myself when I was discharged that I was going to help everybody that asked me.”

As told to Jean Kilby