An Evening With John Lewis

They buried John Lewis today. (July 28), and nearly 60 years gone, but it did jog my memory. I’m sure he would not have remembered our brief meeting, as the incident was soon overwhelmed by events.

It was May 4, 1961, I had to look it up, but I was at home on my day off when I received a phone call from Charles Sherrod, inviting me to come to a small din-ner at Virginia Union Theological Seminary. Richmond was the first stop on the itinerary of the Freedom Riders, and they would all be there.

The brief background is that Charles Sherrod had led the student sit-ins at the lunch counters in downtown Richmond the year before. Charles was a young mover and shaker in the nascent Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (Snick) and a foot soldier in Martin Luther King’s movement. I was the police re-porter of the Capital city newspaper, Richmond News Leader, and had covered the sit-ins. As a reporter, one had to tread carefully, very carefully, in covering racial matters, but I had managed to make my way without criticism from either side. I was trained to play it straight. Anyway, Charles apparently trusted me, and he was astute enough to realize that news coverage was coin of his realm.

I knew nothing of the Freedom Rides, although I had heard of Jim Farmer, the organizer, and of one of the other riders, James Peck, a reputed wild radical, particularly by Richmond standards. Never no mind, I wouldn’t find out anything staying at home so it was off to the dinner.

At the dinner, I learned that the group was embarked on traveling by bus bound for New Orleans, challenging Jim Crow laws on racial segregation in the Deep South as they went. They had Supreme Court laws (Morgan and Boynton) to comfort them, but little else.

In Virginia, that had proved so far not to be a problem. Partly because of Charles Sherrod and his fellow students, the first layer of the onion had been peeled back. Before the sit-ins, black and whites, by law and by custom, were forbidden to sit down together. The department stores now accepted blacks at their counters (and let black women try on Easter hats before purchase.) Vir-ginia was slowly giving in to desegregating (rather than closing) their schools, and the Richmond police had chosen to brook no violence.

At the dinner, Charles spoke, as did Farmer, and each of the Riders briefly described himself/herself without providing much information in depth. I probed as much as I could, taking careful notes, but I realized there was much to be revealed.

The Riders, a mixture of black and white, young and old, religious and secular, Northern and Southern, were civil rights warriors, veterans of many protests, and some were remarkably old. They undoubtedly showed up in FBI records. Thirteen in all. Seven blacks and six whites. Farmer, black, was the leader. Peck, white, was second in command. Three were young black students. Lewis, 21; who grew up on an Alabama tenant farm; Charles Person, 18; and Hank Thomas 19. Other blacks included Jimmy McDonald, 29, a black folk singer; The Rev. Ben (Beltin’ Elton) Cox, 29; and Joe Perkins, 27, a CORE staffmember. CORE, the sponsor, was the Congress on Racial Equality.

The white contingent contained, Walter, 61, and Frances, 57, Bergman, with a long record as civil rights protesters; Ed “Blankenheim, 27, a Parris Island grad-uate; Genevieve Hughes, 28, a CORE staffer; and Albert Bigelow 55. Bigelow was a hard-core peace activist, who had captained the Golden Rule, a 30-foot ketch which had set out to sail into the drop zone protesting nuclear testing at Eniwetok in the Pacific.

What a field day Chaucer would have had, but this was no Canterbury.

The seating plan was laid out by Farmer. Each group was made up of one black Freedom Rider sitting in a seat normally reserved for white, while one interracial pair of Riders sat in adjoining seats. Two buses. One rider on each bus served as a designated observer, aloof from the others, and served as a contact to report back to headquarters in case of trouble and to provide bail, if necessary. Generally, bail was avoided, with protesters preferring to “fill up the jails” in Gandhi fashion.

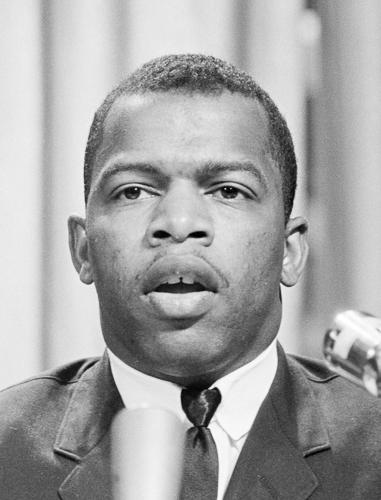

I was struck by one black who stood out because of his youth and demeanor. He was 21, younger than I was (25). He had a quiet, determined, no-back-down look, solid if not demonstrative or flamboyant. He told me that he had been in protests before without offering details. (He was part of the Nashville Movement.) He reminded me of people I had met in the Marine Corps. His kit bag carried three books, one on Gandhi, one by Catholic philosopher Thomas Merton, and the Bible.

That was John Lewis.

Most of that evening has faded in my memory, except for the music. I was amused by the song: “If you miss me from the back of the bus, and can’t find me nowhere, Come on up to the front of the bus, I’ll be riding up there.”

Then they turned up the volume and launched into “We Shall Overcome.” I lost my objectivity for a bit and joined in. That was close to home. My father was a labor leader and the song was a stable household melody among the union songs that he played. It had morphed many times, but became SNCC’s anthem in the early 60’s. Its usage traced to black labor protests among cigar workers in Charleston, South Carolina in 1945.

I also contemplated what these Freedom Riders were setting out to do. Not long before, I had been through Parris Island boot camp and had some appreciation of what a human being could withstand. Much more than they thought, I found—it was a mental thing.

The Island provided an organized taste of toughness and the trait dominated discussions In the Marine Corps. But 98 squat jumps differs from a punch in the face, as Mike Tyson has pointed out (“Everybody has a plan until they get hit in the mouth.”) But that experience would not begin to cover letting yourself be beaten—hit in the head with a club and much worse—without reacting. A special discipline.

The older white passengers seemed particularly vulnerable. The white woman would have her own devils. John Lewis drew my particular attention. He was young and looked strong, and bore a resolute look, but still...

Well, that ’s it. John Lewis went on to that bridge at Selma, Alabama, where his head was cracked open. He carried on. His story is well known. I never encountered anything so dramatic, and wonder to this day how I would have fared with Gandhi—or the Riders. I have always admired John Lewis in the same way I admired Chesty Puller.

The following day, I went to work and wrote a four page story recounting of my time with the Freedom Riders, using as much a downplayed, just-the-facts style as I could manage and still tell Richmond’s readers who these people were that had ridden by. I’m sure they would have liked to have known, even if they heartily disapproved. I didn’t mention We Shall Overcome. I turned the story in, and later was informed by the city editor that he was thanking me for a good story and a job-well-done but that he had “spiked” my copy. It would not see the light of day. I nodded. He didn’t have to tell me why. The News Leader, where Douglas Southall Freeman, he of Lee’s Lieutenants, once reigned as editor, was still very much part of the South. It wouldn’t lie, but it wouldn’t tell all the truth.

The Freedom Riders moved on, passing through Virginia without major incident. At Rock Hill, S.C., it all changed, as recounted in Raymond Arsenault’s excellent book, “Freedom Rider.” Ironically, the lack of advance publicity along the way had worked in favor of the Riders from the point of view of intervention, although contrary to their overall purpose to provoke publicity. But the KKK finally tumbled. Eventually, the Freedom Riders banged their way South to the Selma bridge. The beatings were top of the evening news, the cover of Time. The city editor approached me and asked if I would mind rewriting my earlier piece to reflect that these news magnets had stopped in Richmond. I minded. I declined. I didn’t have to tell why.

Soon after, upon reflection, I decided internally that if I wanted to continue following the civil rights story, I was going to have to do it from a different venue than the newspaper I was on. Journalistically, the catnip of a story becomes poison with suppression. Meanwhile, I had to swallow the frustration; I had a child on the way, and needed a job. I asked to be switched to other coverage, and I was introduced to the business/financial beat, with a back-up in politics.

I covered several more civil rights protests after that, but business/finance be-came my muse. John Lewis stayed the course.

James Hanscom July 28, 2020 Harrisonburg, VA