The Bicycle Repairman

--by Jim Hogan

The story ran in the Spokane newspaper and was well received. He told my son-in-law if he had relatives visiting Spokane, he would give them a tour of the Grand Coulee Dam.

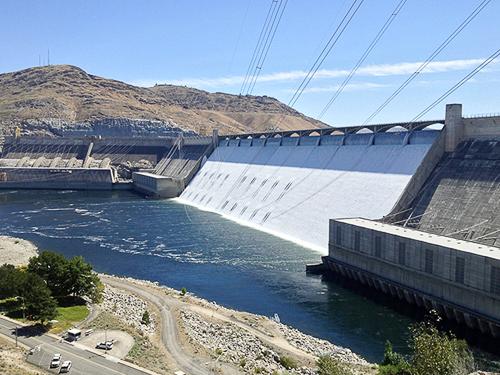

My wife and I visited our daughter in Spokane, and her husband asked if I wanted to tour the dam. I told him I was eager to see the dam because I had read about it. My son-in-law called the repairman and arranged for us to get a tour of the dam the next day.

We went to the small town and looked up the repairman who took us to the dam about 30 miles away. Parking in the employees’ lot, we transferred to his pickup truck. He took us to the bottom of the dam, where only employees were allowed. When we got inside the huge dam, he showed us long wet corridors inside the dam. My guess was we were over 100 feet below the water level in the dammed-up Columbia River. As we walked the long corridor, I asked our tour guide why the concrete was wet. He explained the wetness was due to water condensing on the walls due to the cold temperature in the corridor and the cooling water lines inside the concrete. He explained the pressure from all of the concrete above us was so great that it was necessary to cool it, or the heat would destroy the integrity of the concrete and cause it to crumble.

We finished the bottom of the dam tour, and then he toured us through the room where the water went through the vortex. The vortex directed the water into the turbine blades, which drove the armature and generated the electrical power. One vortex was open for maintenance, and there was a string of lights inside the vortex, allowing us to see the inside of the vortex. He explained that the lake water came in through a 30-foot diameter opening. The vortex was reduced to a 10-foot diameter opening directing the water against the vanes controlling the amount of water to drive the turbine or to shut it off. We looked inside the vortex through a reinforced access door, and all we could see was a black hole. He explained the vortex had a coating of black rubber to prevent eroding the steel casing. The repair work was to replace some of the rubber, which had worn down over time.

He took us to the room where large hydraulic cylinders controlled the vanes. There were eight turbine controllers in one long room. He told us each of the vanes was controlled by an electrical system in a control room. He explained manual controls could control the vanes if the electrical systems were not working. I had the opportunity to look up above us and saw the people on the standard tour looking down on us. He explained, the general public was not permitted to tour the control room area. I knew then our tour was exceptional.

He took us to another long room where the tops of each turbine rose above the floor level. The room was designed so the armatures and turbine shafts could be removed from their casings and set down on the floor where maintenance was performed. We were fortunate to see one turbine being maintained. The shaft looked to be 4 feet in diameter, and the armature was at least 60 feet in diameter. He told us they had to use a 200-ton overhead crane to lift the armature assembly out of the casing.

I asked him why there was so much copper tubing on the armature. He explained the heat energy developed between the armature and the stator to melt the armature permanent metal sections. The water in the copper tubing was necessary to cool the armature. He also explained that the run out of the shaft was monitored continually, so if a problem showed up, they would catch it, shut down the turbine, and perform maintenance. He said if the shaft varied more than one thousand of an inch run out, the turbine was monitored more closely. At two thousand of an inch, the turbine was shut down.

I noted several 4-inch copper cables leading out of the building and up the rock formation side on either side of the dam. I asked him what would happen if one of those cables shorted out while we were standing near them. He said not to worry. We would be instantly vaporized.

I noticed some metal plates sitting on the floor in a circle near the armature under repair. When I asked what they were, our guide explained they were the bearings that supported the shaft and armature's weight. My guesstimate indicated the weight was 50 tons, probably more. He showed us the ten metal bearings that supported all the weight. They were one-inch-thick Babbitt bearings. He said they were immersed in oil, and the oil was cooled to prevent the bearings from melting.

We went outside the turbine building. Our guide had to ask permission to tour the control room controlling each of the turbines and the electrical distribution system. Permission was granted to enter the dimly lit, quiet control room. We were able to ask a few questions of the technicians who were making changes using light pens. One explained they were sending electricity as far as Los Angeles. I knew enough about electrical line losses when trying to distribute electricity that far. He explained the electricity was sent as direct current to Los Angeles, where it was converted into alternating current. We exited the control room and ended the tour. When I asked the bicycle repairman about his job at the dam, he said he was the Grand Coulee Dam's Chief Engineer. That explained why we were able to go where other people were restricted from touring.

It was a memorable tour, and we thanked the generous bicycle repairman for all that he did for the kids in his home town and the exceptional tour of the dam.